The critical flaw in Worcester's bus system

WRTA's hub and spoke model is holding it back

On paper, Worcester’s bus system seems solid: it has 26 fixed routes serving over 4.5 million annual riders completely fare-free, and most buses connect with each other through an impressive central hub with indoor/outdoor seating, wayfinding, and quick access to downtown, Polar Park, and the MBTA commuter rail. The Central Hub is a piece of infrastructure Worcester should be proud of—yet it is also holding the system back.

The WRTA, Worcester’s regional transit authority, relies on a strict “hub and spoke” model: all numbered routes start at the hub, then snake through Worcester and stop at the outskirts of the city. Just like the spokes of a wheel, all transit routes originate at the center.

This approach undoubtably has its benefits. First, it’s theoretically possible to get from any bus stop to any other bus stop in either a one-seat or two-seat journey. Second, every route offers a connection to MBTA Union Station. Third, the WRTA can focus on constructing and maintaining only a single hub for their entire network.

And for smaller networks with infrequent service, all of these benefits are potent! The hub and spoke transit model is a good place to start for agencies who want a unified network from day one. However, this model quickly gets in the way once you expand service.

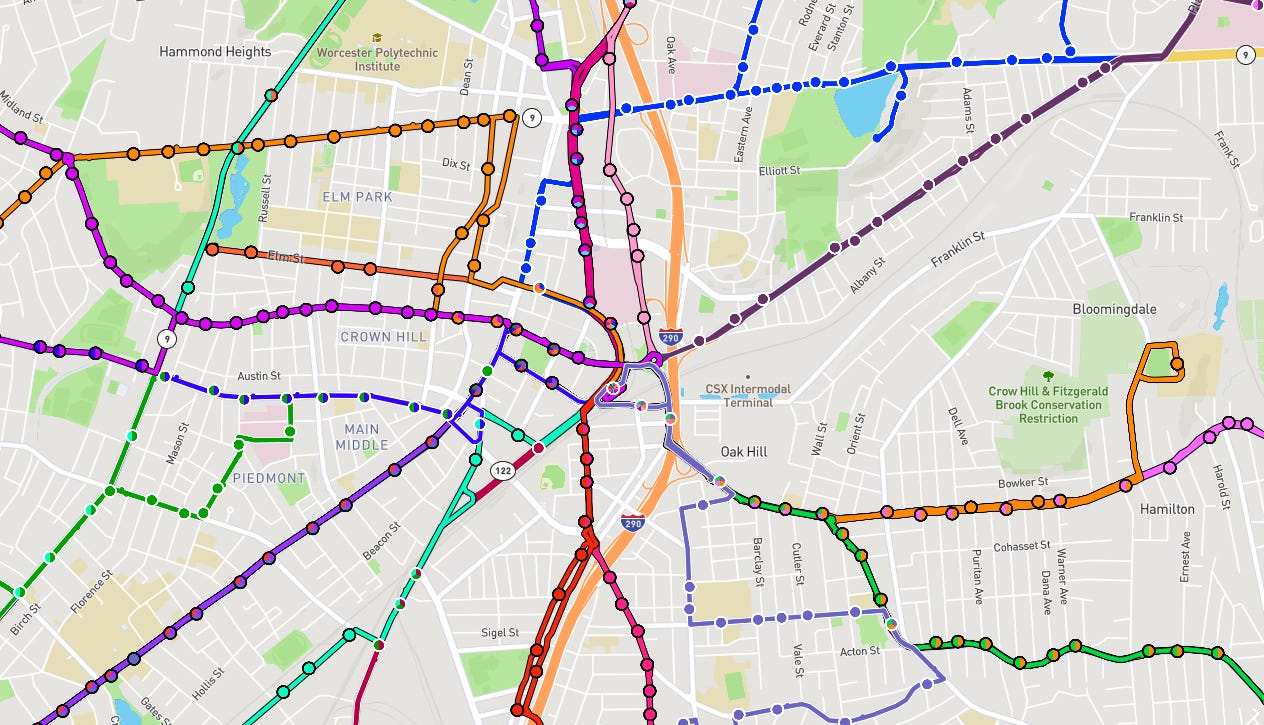

I think this is best illustrated by Worcester’s existing route network:

All lines start at Central Hub, maybe travel on a “trunk” with other lines, then split off. This introduces a couple design quirks that quickly snowball into fundamental issues.

All-in on central trips

This model prioritizes central and linear trips, making neighborhood-to-neighborhood trips much more time-consuming. For example, getting downtown from Elm Park is easy: routes 3 and 31 offer a direct connection that is competitive with driving. But getting from Elm Park to Bell Pond—usually an 8-minute drive—becomes a 40-minute bus commute with a transfer at Central Hub.

Because all lines start and end at Central Hub, no buses continue through downtown to the other side of the city. There’s nothing stopping WRTA from connecting Route 26 and Route 19, the city’s most popular routes, into one high-frequency north-south line, but the hub and spoke model keeps this from happening. What could be a one-seat ride is instead a two-seat ride, adding needless time for passengers who want to travel down the entire corridor.

The current alignments force the 26 down a desolate Major Taylor Boulevard and the 19 through congested Front and Franklin Streets. Switching this route’s alignment to Main Street would serve denser development and make for a more pleasant walk to and from the bus stop.

An even more congested downtown

Because every line routes to Central Hub, stops around the hub are shared by many lines, adding needless congestion. Take these stops on Foster St and Franklin St for example: they both are served by six different buses!

Larger cities with dedicated bus infrastructure can handle this activity; Worcester is managing for now. But any major increase in frequency will quickly overload these stops. If lines instead took various routes through downtown, stops could stay close without being shared by too many lines.

The corridors themselves often get overloaded in the same way. With no dedicated infrastructure, buses entering and exiting downtown get stuck in traffic, slowing everyone—walkers, rollers, transit riders, and drivers.

A barrier to higher frequency

Even though Central Hub has eight bus bays and two entrance/exit points, it is quickly nearing capacity. Ridership is up 140% from pre-pandemic levels—a quite unprecedented increase—and raising frequencies is the easiest way to handle it. In theory, this is simple: buy more buses and hire more drivers. But higher throughput exposes some painful pinch points.

Central Hub is already limiting the system its current state. In April, the WRTA tried to achieve clock-face scheduling1, but congestion at Central Hub and certain corridors made this tough.

Let’ do some napkin math: with 30-minute average frequencies, two buses per hour depart Central Hub on each line2. With 26 lines, that’s 52 buses an hour, or about 0.87 buses per minute. Tough, but manageable.

But at 15-minute frequencies, you get 1.7 buses per minute. If each bus stays at a bay for five minutes, that’s about 8.7 buses at the station at once—too many for eight slips.

And that assumes perfectly even spacing and no new routes, which is unlikely. Even if buses spend less time at the hub, you’re still dumping over a hundred buses into downtown intersections each hour. That would wreak havoc on traffic, especially during rush hour.

The (not so easy) solution

So, what do we do to fix this? The solution is simple: not every route should stop at Central Hub. If two routes share a corridor (like the 3 and 24, and the 19 and 26), combine them into one route. This is called a transfer-based or mesh network, where routes form a grid instead of spokes. From downtown, Boston’s metro looks more mesh than radial: stations rarely connect more than two lines, but you can transfer from any one line to any other line (except from Blue to Red, boo!).

This way, riders can connect to any line they choose without having to navigate across a congested central station.

Of course, some riders still need to get to Union Station or Central Hub. These are key destinations. But it’s only a deal-breaker if there are no transfers available and the nearest stop is still far away. If you’re on the hypothetical 19/26 bus and need to get to Union Station, you can get off at City Hall and walk 10 minutes to the station. Or, if you’d rather ride, you can catch another bus the rest of the way. If frequencies are 15 or 20 minutes and multiple lines serve the corridor, you won’t wait long.

So, the key is to have some buses that stop right at Central Hub and others that run radial routes which connect. This way, some lines could run more direct on corridors like Park Ave or Route 9 or Main St while others serve Central Hub and Union Station. It’s a win-win. If only Worcester would prioritize its own bus system!

Clock-face scheduling is a type of scheduling where transit arrives and departs at the same points in every hour throughout the day. A bus that arrives at a stop 0, 15, 30, and 45 minutes past the hour is said to be clock-face scheduled, same with a bus that arrives every 20 minutes at 5 minutes, 25 minutes, and 45 minutes past the hour. This makes it a lot easier for transit riders to plan their trips around transit; they don’t have to memorize a complex schedule and instead just arrive at a stop at a certain point past the hour.

This is a rough estimate—some buses run every 15 or 20 minutes at peak times while others run every hour. I wouldn’t be surprised if the average frequency was more like 40 minutes.

![[move]worcester](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!Fywr!,w_80,h_80,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fc2d0ae5a-1209-4df0-bd50-f6a02caca397_1280x1280.png)